Full disclaimer: I have never experienced the pain of infertility. I have never been a parent.

However, I know that receiving a diagnosis of infertility is a devastating loss. It’s natural to feel angry, sad, disappointed or a combination of a bunch of different feelings. You may want to start the process of becoming a parent through other means as soon as possible, in an effort to fill that aching, empty space in your heart.

But, as an adoptee, I will say this:

Please don’t start the process of adopting a child until you have fully grieved your infertility, let go of your initial dream of having a biological child, and are truly ready to adopt.

Why? Because, when you pursue adoption, your infertility journey will affect more than just you.

Adoption is not a solution for infertility. Pretending it is — without doing the hard, personal work — will just set you and your future child up for failure.

You’ve probably heard it time and time again from your infertility counselors and adoption professionals. But I think you should hear it from an adoptee — someone who will be forever changed if you are unable to move forward from your losses.

Why Healing After Infertility is Important for You

Again, I’ve never felt the pain, anger and loss of infertility. But I’ve watched it take its toll on my parents, friends and family members. Even just having seen the effects secondhand, it’s clear that this is often a diagnosis that causes lasting emotional and psychological damage.

About 1 in 8 couples will struggle with infertility. That’s a lot of people walking around with a lot of pain on their hearts.

This is a loss, and as such, you may experience the stages of grief. As hard as it is to believe, this is actually a good thing, because it means you are processing your loss and are on the road to the final stage: acceptance. And only once you feel acceptance should you start considering adoption.

But that means you’ll actually need to grieve your infertility first.

If you don’t, it could cause serious mental, emotional and physical harm to yourself and to those around you. You may start to resent your partner, your emotions might develop into depression, you risk not feeling able to find happiness because of the lingering hopes and dreams of “maybe we’ll still get pregnant,” and the stress can take a toll on your physical health.

As scary as picking apart those difficult emotions probably feels, we all know how much strain unresolved issues can also place on relationships — the relationship with your partner, with yourself, with your friends who seem to easily have children and eventually, with your own child.

Hopeful parents who haven’t fully grieved their infertility and moved forward can’t wholly embrace and become excited about the adoption process. They might feel like they are “settling” for their “second-choice” way to build a family, and that’s not fair to them (or their child). Not only do you need to let go of the dream of having a biological child, you need (and deserve) to actually be excited about adoption as its own equally wonderful way to build a family.

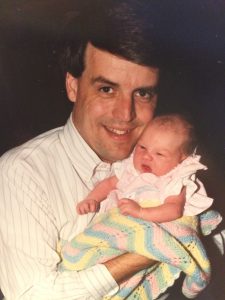

My own parents struggled with infertility for years. Before they moved to adoption, they’d been married for nine years, and five of those nine years were spent pursuing infertility treatments. My dad was ready for adoption, but my mom couldn’t let it go yet. When sharing her story, she said, “Although I was frustrated as well, I was optimistic that ‘next month’ we would be pregnant. Finally, in the fall of that year I agreed we would visit with a social worker at the agency, but still thought of adoption as ‘Plan B.'”

It was only when she learned about open adoption that my mom was as genuinely excited about adoption as my dad was, and began to see adoption as Plan A. But she had put off being able to have her dream of parenthood for so long, because she couldn’t move on from her infertility grief.

Many of the people that American Adoptions have helped turn into parents have had similar journeys. A lot of them spent years pursuing infertility treatments, then described letting go of infertility grief and embracing adoption as a “relief.”

Maybe adoption isn’t the answer for you, but staying stuck in grief isn’t an option. Whether you decide to build your family through adoption, explore other options like surrogacy or ultimately decide to live child-free, it’s important for your own quality of life to work through your feelings and let them go.

It will undoubtedly take you time, lots of support and maybe even a little professional input. Do what you need to do to address your grief. Take your time. Take care of yourself, and take care of your relationship.

Why Healing After Infertility is Important for Your Future Children

It may be tempting at different points in your winding path to parenthood to think that having a child by any means will heal that hurt and that empty place in your heart and home. But adopting a child won’t “fix” anything.

There is no replacement for your original dream of conceiving and giving birth to a biological child. It sucks, but it’s something you must acknowledge before adopting.

Someday, you may be ready for a new dream — the dream of having a child through adoption. This is not at all the same dream. That doesn’t make it any less special, but it is an entirely different kind of special. Are you ready for that? Are you fully educated about what it takes to raise an adopted child? Because, while the love will be just as strong, it’s not the same experience.

If you move into adoption too quickly and you haven’t fully grieved or accepted your infertility, it will affect more than just yourself — it can have lasting consequences for your children.

An Adopted Child Shouldn’t Feel “Second-Best”

Your adopted child will feel you brush through her curly hair, looking at your perfectly straight hair. She may worry that you wished for a daughter with your hair. She’ll wonder if you wished that she had your singing voice, or if you wished that she shared your height.

While this can be true for all children, it can be a particularly tough silent question for adopted children. No child wants to feel like they’re second-best, a consolation prize or a backup plan.

Of course, that’s the last thing any parent ever wants their child to feel. But if you hold onto any lingering infertility grief, your child will notice, and it’ll hurt. Quite a few adult adoptees have discussed how their parents inadvertently made them feel “second-best” because they didn’t seem able to move on from grieving their infertility.

Adoption may not have been your first choice. That’s OK! But it does mean that you’ll need to spend a little extra time reassuring your child that you wouldn’t want them to be anything other than what they are. In order to do that, you have to come to terms with your own fertility losses.

An Adopted Child’s Differences Should Be Celebrated

Parents love to see similarities between themselves and their children. When you’re an adoptive parent, your child would share physical their traits with their birth parents — not you. This can be hard to come to terms with, but it’s important to come to terms with it before pursuing adoption, not after.

Celebrating your child’s uniqueness and differences will affirm their validation, and their place within your family. In order to be able to do that, you’ll need to have moved on from wishing for those genetic similarities.

Adopted children need to know their stories, and they need to know that it’s OK to talk about adoption. They’ll look to their parents to understand how they should feel about their adoption, and they’ll have questions. It can be hard for adoptive parents to openly and positively talk about their adoption story (and it can be hard for them to watch their children interact with their birth parents) if they’re still dealing with the lingering grief of infertility.

Often, one of the reasons why adoption isn’t openly talked about in the homes of adopted children is because the parents are still uncomfortable. There is a temptation to ignore the adoption and unconsciously pretend that the child entered the family through “traditional” means. But this shoves the parents’ grief under the rug, and even worse, it makes their child feel as if being adopted is shameful or secretive.

My Own Experiences

My adoption situation is pretty much the ideal. I always felt loved and wanted by both my birth and adoptive families.

However, even their love couldn’t shield me from the fact that most families are created biologically, and mine was not.

However, even their love couldn’t shield me from the fact that most families are created biologically, and mine was not.

It’s hard to notice how much of our day-to-day is steeped in the assumption that a child is biologically related to their parents. From school family tree projects to strangers commenting on perceived similarities between myself and my (adoptive) family members, it can make even the most confident kid feel a little self-conscious. For transracially adopted kids who don’t look like their parents, these types of experiences are more frequent and more uncomfortable.

As I got older, listening to the various people in my life struggle with infertility was hard. I had a difficult time watching them try everything to get pregnant. They stabbed themselves with needles, took hormones and took their temperature. I tried to be understanding and supportive, but there was always a small, angry voice in the back of my head that screamed, “What am I, chopped liver?”

Rationally, I know that pursuing that first dream of having a child biologically is important, and that adoption is not for everyone. I know it’s not necessarily a “fair” feeling for me to have. But hopefully you can understand why their reluctance to pursue adoption hit me a little close to home.

When you’re an adoptee, viewing the world’s preoccupation with having biological children is hard. It’s probably hard for you, too, now that you’re coming to terms with the fact that you may never have a biological child.

For me, it feels like the world is saying I’m the backup plan: “Well, if I can’t have this, then I guess I’ll do that.”

We know the ways that infertility hurts hopeful parents. But you might be surprised at the ways infertility can hurt adoptees.

Fortunately, an adopted child’s feelings don’t exist in a void — and you can take easy steps to avoid them feeling the effects of your infertility struggles.

So, What Can You Do for Your Future Child?

If you’re thinking about adopting after you’ve had enough time to grieve the loss of infertility, you’ll naturally want to avoid ever making your child feel second-best.

Here are a few tips that may help you be the best possible parent to your future child:

- Correct strangers who praise perceived similarities between your child and other members of your family.

“Thank you, he does have beautiful eyes! But he got them from his beautiful birth mother.”

“He didn’t inherit that from me, no. He’s just talented, and he worked hard at it!”

- There are ways to draw positive similarities between yourself and your child that don’t involve genetics.

“You’re so funny! Did you learn your sense of humor from your dad?”

“You and I both know just about everything about soccer.”

- Encourage and embrace your dissimilarities.

“I wish I were as brave as you!”

“You’re so gifted at music. Maybe you could teach me!”

When you’re a potential adoptive parent, it’s your job to reassure your child — that your similarities and your differences are equally celebrated, and that you would never trade them for a biological child. But, to be able to offer those reassurances in honesty, you need to have fully let go of that first dream of a biological child. Adoption is your new dream, not the option you “settled for.”

—

When you choose adoption, there are some unavoidable facts:

- Your child will not be biologically related to you or your partner.

- You will not experience pregnancy or childbirth with your child.

- And you will always have a connection to your child’s birth family — a connection that you’ll need to be ready to embrace and encourage.

These can be incredibly hard truths, especially after you’ve already experienced the hard truth of infertility.

These can be incredibly hard truths, especially after you’ve already experienced the hard truth of infertility.

But, take it from an adoptee: They’re truths that you’ll need to fully accept in order to love an adopted child — and for your child to feel the love and support they deserve, no matter where they came from.

Diana Watts is an adoptee and a staff writer at American Adoptions. You can read more about her adoption story here.

Thank you for your perspective. I appreciate the insight and the self disclosure. As an adoptive mom who experienced infertility I think that it is important to remember that no grief is entirely resolved. Just like adoptees and birth families experience grief that ebbs and flows even in a “positive” adoptive family situation, infertile parents may experience grief after adoption even after being in a better place previously. Of course that grief is not a responsibility of the child to address, but it may be unfair and unrealistic to say infertile, potential adoptive parents are no longer allowed to experience grief once they adopt. Sensitivity should be on all ends.